MEET BRAD ASCALON

“You fight against the grain however you can,” says Brad Ascalon, sitting in his home studio on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

QUICK FACTS

Founded a studio in 2006. Collaborated with Bernhardt, Shu Uemura, Esquire and Intel.

FOLLOW

SHOP

Univers Series – Bath Set Univers Series – Office Set Univers Series – Bedroom Set

CREDITS

Written by Alexis Cheung

Photographs by James Chororos

In collaboration with Freunde von Freunden

"I’ve always had an appreciation for craftmanship, materials and longevity. Everything that my grandfather and father had ever done wasn’t trend driven; it was permanent. That’s a huge factor in choosing how and what I design. "

"Every single project I do. I welcome the unknown.”

I realized that there’s not much difference between music and art and design. They all come from the same place.

For Brad, those words hold personal meaning—although he hails from a lineage of designers, he took brief detours into advertising and then music, before finally earning his Master’s degree in Industrial Design from Pratt.

In 2006, Brad launched his eponymous studio; not long after, L’Oreal, his first major client, came calling. He’s since created furniture and packaging designs for clients including Ligne Roset, Design Within Reach, Bernhardt Design and Shu Uemura, among many others. And while he’s deviated from his father and grandfather’s handmade methods, “I’ve always been taught the importance of craft and craftsmanship,” he says. “I still put that line of thinking into my work.”

He applies similar energy to his life outside of the studio, reflecting on a deep love of music and an appreciation of the unknown, all while Charlie Parker, his beloved dog, lays curled at his side.

Your grandfather and your father are both artists and designers. How has coming from a lineage like that influenced your work?

My grandfather was a sculptor and industrial designer who is considered by many to be the father of Israeli art deco. He had a small decorative arts company in the 30s and 40s that did religious objects but also secular ones. My father took it a different direction with large scale art: stain glass, mosaic, sculpture. I took it my own direction, as well, by going into product design. I’ve always had an appreciation for craftmanship, materials and longevity. Everything that they’ve ever done wasn’t trend driven; it was permanent. That’s a huge factor in choosing how and what I design.

What drove you to dabble in other fields—namely music and advertising—before landing in design?

I was in advertising out of college as an account coordinator for Broadway shows. I thought that would be a segue into the music industry and it wasn’t. But I made my way into the industry, working for Atlantic Records in the marketing department. That was an awesome job, but then my division—which focused on alternative genres of music like classical, avant-garde, jazz, electronic, the non-money makers—was let go. That’s when I decided to leave the industry.

How did that experience lead you to become a designer?

I had a heart-to-heart with my father. He always tried to push architecture on me and I never really listened. But as I started looking into architecture schools, I discovered this field of industrial design. The idea that people spend time and energy designing, producing, developing, all these things around us—I started becoming fascinated by that. I loved the notion that this field we take for granted is everything. Everything we use on a regular basis starts somewhere, and that somewhere is the design of it. So I decided to study industrial design at Pratt.

.

Did you think you’d be a designer when you were a kid?

Not at all. The reason I went into advertising is I wanted to be a copywriter. Even before advertising, I wanted to write music. I had a band in college. We recorded a couple of albums, wanted to be big rockstars. Our biggest show was opening for Chicago.

What was your first job out of design school?

I was very fortunate. When I finished school, I started putting a portfolio together, wondering what the hell I was going to do. Because I came from the corporate world, I knew that I wanted to have my own studio, but that’s easier said than done. So as I started putting this portfolio together, my phone rings and it’s this guy Robert Bergman who was the creative director of special projects at L’Oreal. He told me he saw some of my design concepts online, and for the next 18 months, I was designing for a number of brands under the L’Oreal umbrella. I was very fortunate in having that steamroll my studio because it kept me busy and paid the bills when I was starting to go out on my own.

Aside from craft and materials is there anything else you consider as you design?

My approach to design is: I’m not designing for me. I’m designing for everyone who is going to use the product; I’m designing for the people who are producing it, marketing it, selling it. The process is really a dance: I have to impart their DNA into my own DNA. Then we go back and forth until we find that perfect solution. Design is problem solving. Design is looking at the needs of the marketplace, your customer, your client. It’s developing products that will be successful, increase market share, and will have users think of their products differently.

What is one of your career highlights or favorite things you’ve done?

I’m always very excited about the projects I’m working on. When I get that design brief, if I don’t feel a little scared—like I have no idea what I’m going to do or how I’m going to approach it—then it’s not worth doing. I want to learn from every single project I do. I welcome the unknown.

Why did you want to work with OTHR?

The idea that a manufacturer wouldn’t have to stock inventory and not have its own facilities to manufacture is pretty brilliant. OTHR are the first to say, there’s a business model here that hasn’t been explored.

I realized that there’s not much difference between music and art and design. They all come from the same place.

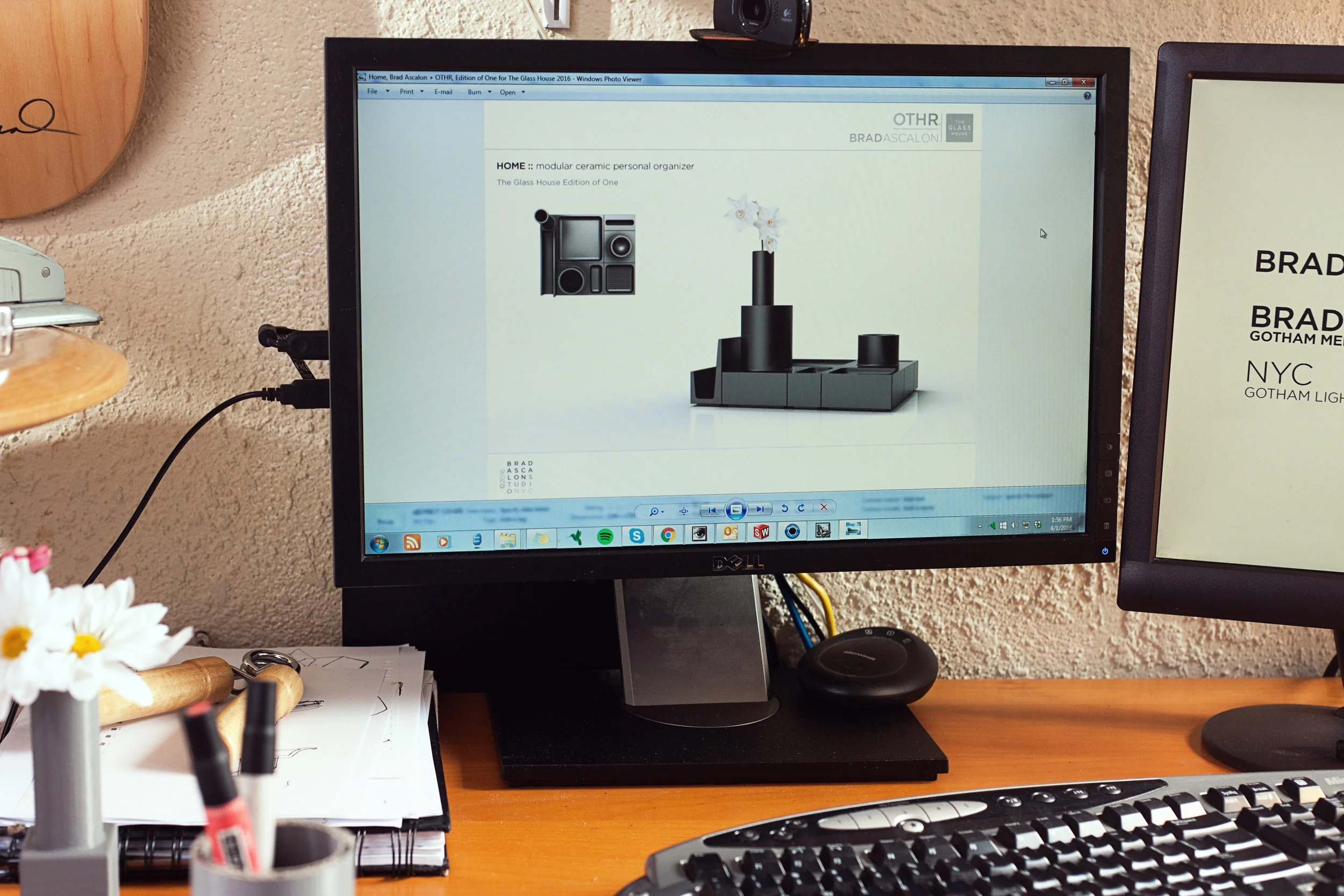

Tell us about the pieces you designed for OTHR.

It’s a three piece set for your office, bathroom and bedroom. But for the most part, we didn't want to define what each component is. For example, here’s a tablet holder—but there’s no reason you can’t use it for a phone, business cards or letters to mail out. This is a pen holder, but it’s also a toothbrush holder. Everything is defined by how you use it.

The fun of it is that you don’t have to keep it as this rectilinear form, you can create this beautiful arrangement however you see fit. You’re the designer.

To close: who’s your biggest design influence?

The composer Philip Glass. He’s called a minimalist but I don’t see his work as minimal. I see his work the same way as I see my design work: it’s reductionist, or only what’s necessary, but still melodic, still emotional. It’s extremely complex and mathematical.

I started listening to him when I was in college. All of a sudden, it clicked—I realized that there’s not much difference between music and art and design. They all come from the same place. They resolve themselves in the same ways. Whether I’m playing the piano, or designing, or painting, even cooking, I’m doing the same thing: it’s balance, it’s texture, it’s knowing when you’re done and when it’s right.